Setting the right course

Mapping out a strategic plan for the year ahead

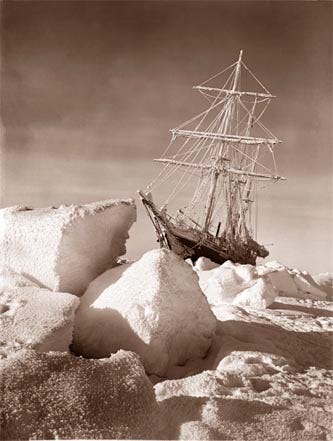

When Ernest Shackleton and his crew of 27 men and 69 dogs sailed for Antarctica in December 1914, they had an ambitious goal: to complete mankind's first-ever land-crossing of the frozen continent. Unfortunately, after sailing through "pack ice" for weeks, their vessel, the Endurance, became lodged between ice floes, forcing them to abandon ship.

Still far from land, the men camped for months, often in blizzard conditions, on sheets of ice that moved and cracked beneath them. Finally, in April 1915 the ice cleared enough to allow them to sail lifeboats to Elephant Island, an uninhabited ice-covered island off the coast of Antarctica. It was the first time the men had set foot on solid ground in 497 days, but their ordeal was far from over.

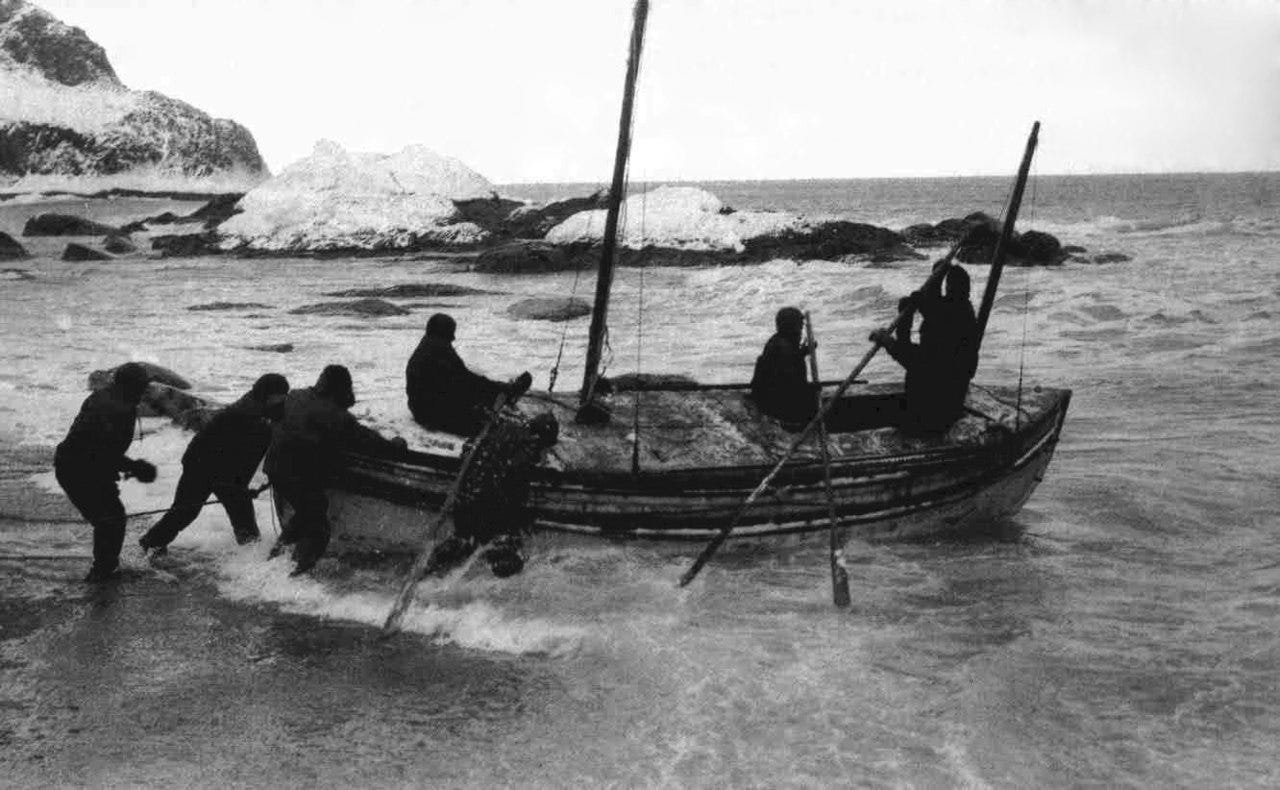

If they had any hope of being rescued, they needed to find their way back to civilization. So Shackleton and five members of his crew set out in one of the lifeboats, christened The James Caird, on a journey to South Georgia—a whaling outpost some 800 miles northwest of where the crew was marooned.

By any stretch of the imagination, this journey should have been impossible.

It was the equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack—all while navigating icy waters, gale-force winds, and constant squalls—and doing so on almost no sleep, little food, and almost unbelievable pressure. The men knew that even a slight miscalculation in their route would send them off to sea, where they would undoubtedly perish along with the 21 men waiting behind to be rescued.

In fact, the story of Shackleton's Antarctic expedition could very easily have been remembered as a tragedy, but instead, we remember it as an epic tale of survival against all odds. And yes, it is because Shackleton and his crew had ungodly amounts of grit, and determination, and toughness; but they also had Frank Worsley.

He was the captain of the Endurance, known for his rare ability to navigate to even the most microscopic islands on the map. Fortunately, Worsley and his trusty sextant (a navigation device) were aboard the lifeboat setting the course of South Georgia. Again, against almost all odds, Worsley was able to triangulate into accurate measurements based on the position of the sun (which was rarely viewable) and the horizon (which was also almost impossible to see given the constant swells). Somehow, the course that Worsley set proved to be spot on, and The James Caird reached the shores of South Georgia after 16 rain-soaked, frost-bitten nights. I'll leave the rest of this heroic tale for you to discover yourself in Alfred Lansing's masterful telling of the story in the book Endurance.

In the meantime, let's talk about navigating something else. The year in front of us.

We know intuitively that we need to set the right course in all parts of our lives—careers, relationships, fitness—before we execute upon our plans. But if you're anything like me, you may find it difficult to find the time to actually do this. Who could blame us when there are endless emails to respond to, endless meetings on the calendar, and endless family responsibilities to attend to? Often, success feels like getting to the end of the day while maintaining sanity. There is always more to do and almost never time to step back and reassess whether or not we are on the right course.

I think of this as getting caught up in the "tactical" while losing sight of the "strategic". Or in other words, focusing all of our time and energy on execution—doing things—and not enough on strategy—figuring what we're trying to achieve and why that's important to us.

This is about the only time of the year when I can actually step away from my day job for a couple of weeks and do some strategic thinking. And even this time of year can be difficult to find the time as family responsibilities, holiday festivities, and lingering 'honey-do' list projects demand time.

But there is perhaps no better use of our time than making sure we are setting the right course—in every part of our lives. So how can we do this? Here are a few ways I'm thinking about it:

It starts with 'why'

Before we think about habits or resolutions or anything so tactical, we need to think about why we are going to do what we are going to do. And to figure out why, we need to answer these two questions:

What is important to me? — On this list are things like: my health (physical and mental), the well-being of my family, my relationships, my financial stability, and for the religiously inclined, my faith. These are big picture items—guiding lights, so to speak. They do, however, require some soul-searching and honesty with ourselves if we're going to truly capture them. I am trying to think a bit more deeply about these this year rather than treating them as a 'check the box' exercise. What other things should be on this list that might not be obvious at first blush, I wonder? For instance, does 'my reputation' make the list if I'm honest with myself? If so, it's worth noting.

Who am I trying to be (in every part of my life)? — Closely related to what's important to us is the concept of identity. I wrote an article earlier this year about how I'm thinking about the various identities I try to embody each day. Actually writing these down (ideally in a place that's regularly visible) helps to remind me of the big picture. If I'm looking at a whiteboard seven days/week that reminds me that I'm trying to be a well-respected writer, a 10 handicap golfer, and an effective leader, I think my chances of actually living up to those identities improves dramatically.

And then it's about 'how'

Once we've nailed these big picture items, it comes down to setting up systems that will enable us to actually become who we are trying to become. For maximum effectiveness, these systems should be:

Identity-focused (as opposed to outcome-focused) — This is a concept that I've cited before from James Clear and his book Atomic Habits. But the idea is that instead of having an outcome or goal like "I want to lose 10 lbs," consider what it would take to confidently describe yourself as "a physically fit person." Then, to figure out the how, you simply ask the question "What would a physically fit person do?" I suspect the answer to that question would involve exercising a certain # of times per week and maybe some diet ground rules. I don’t know why, but there is something that connects with us on a more visceral level when our systems are focused around our identities (This is who I am) as opposed to goals (This is what I'm trying to do).

Achievable — For any system to work, it has to be achievable. If you're trying to be a great writer, for instance, and you identify that greater writers write every day but you then fail at writing even three days in a row, maybe that's not realistic. The best systems are the ones you actually stick with, and as I've discussed in this newsletter before, that allow the magic of compounding to do its work. James Clear and others recommend focusing on the smallest version of the habit or system you are trying to create—do one push-up per day, hit one golf ball per week—as being an effective way to actually make such habits and systems consistently achievable.

So to recap, it’s about establishing the why first and then the how... and then repeating this across the major areas of our lives—careers, fitness, relationships, etc.

Simple, but not easy.

Two thoughts I will leave you with on this subject:

Time — We often begin the year with the best of intentions, but then, as you know, life tends to get away from us. This is why scheduling time with yourself is so critical. I've personally found that when I do not schedule this time in advance, everything slips and becomes much more difficult to achieve. The idea of creating a 'golden hour' is a powerful one, if we can actually make it happen.

Thinking BIG — I believe that most of us (myself included) are not ambitious enough in thinking about who we want to be (which directly drives what we need to do to get there). On a recent podcast, futurist Peter Diamandis spoke with James Altucher about the idea of getting 10 times better vs. getting 10% better. His thought is basically that if you get 10% better at what you're doing, that's good, but it may not even be noticeable to most observers. So I think about this with respect to my job, my fitness, and my relationships. A 10% improvement would be great. I want that. But it won't change my life. Now a 10x improvement (that's 1000% for you English majors) might very well be life-changing. This newsletter goes out to about 150 subscribers today. 10x that would be 1500. Would that be life-changing? I don't know. It could be. I host a podcast for my company and we have about 4000 subscribers. 10x that would be 40,000. Achieving that could be extremely meaningful for the business. Think about it in the context of relationships or fitness, and what a 10x improvement could mean in those areas. Life-changing, potentially. Of course, improving anything by a magnitude of 10 is not an easy thing to do, and we almost certainly cannot achieve this by maintaining the status quo. We need to reinvent it. We need to be creative and think about different ways to tackle our challenges. We need to think bigger. Much bigger. That's what I'm thinking about right now.

As we head into the New Year, I'd suggest that we all should think about how we want to spend our time. And that word "spend" is easily glossed over in this context, but it is exactly what we're doing with our time. We have a finite amount of it. We need to spend it on what's important. And we need to spend it wisely so that we make damn sure we become who it is that we have the potential to become.

Wouldn't it be terrible to get to 95-years-old and look back and think about how we squandered this time we have right now? How we never achieved our potential?

I think so.

But we're in luck. 2021 is a clean slate. An unwritten story. So let's get our acts together. Now is the time to plan what could end up being the most productive, transformational, and rewarding year of our lives.

And similar to Shackleton and Worsley’s 800-mile lifeboat journey, the stakes are high. We only have one shot at this. So let’s make it happen.

Thanks for giving me this space in your inbox this year. I appreciate your time, attention and support.

Greg